By the end of 1937, L. Ron Hubbard had proven he could glide with ease from genre to genre—adventure, western, mystery, detective, and even romance—and was regularly featured in such acknowledged “crown jewels” of the pulp fiction world as Adventure and Argosy magazines. Not bad for a young writer whose first commercially published fiction had appeared only three years before.

By the spring of 1938, with his now well-established stature as a writer—or, in the words of author and critic Robert Silverberg, as a “master of the art of narrative”—L. Ron Hubbard was invited to apply his gifts for succinct characterization, original plot, deft pacing, and imaginative action to a genre that was new, and essentially foreign to him—science fiction and fantasy. The reverberations of that invitation continue to this day.

Read MoreHow this transformation came about is nowhere better described than by L. Ron Hubbard himself in the introduction to his science fiction epic, Battlefield Earth:

“It will probably be best to return to the day in 1938 when I first entered this field, the day I met John W. Campbell, Jr., a day in the very dawn of what has come to be known as the Golden Age of Science Fiction. I was quite ignorant of the field and regarded it, in fact, a bit diffidently.

“In those days when the top brass of a publishing company—particularly one as old [1885] and prestigious as Street & Smith—‘invited’ a writer to visit, it was like being commanded to appear before the king or receiving a court summons. You arrived, you sat there obediently, and you spoke when you were spoken to.”

Street & Smith headquarters,

New York City

What the Street & Smith executives wanted became quickly apparent. One of their magazines was adrift in perilously competitive waters with its stories about “machines and machinery.” The publishing giant had tried everything, even serial name changes from Astounding Stories of Super-Science to Astounding Stories, and finally, with the March 1938 issue, to the name by which it would come to dominate the field, Astounding Science Fiction. The pall of the Depression still hovered grayly over the country and the competition for reader loyalties from other magazines, including those in Street & Smith’s own vast stable, was fierce.

Street & Smith’s top brass knew that in this kind of competitive climate “you had to have people in stories.” They knew with certainty, as well, that L. Ron Hubbard could write powerfully and discerningly about people. They knew it from his work generally, and from the work he had produced for their own magazines, Top-Notch, Western Story, and Wild West Weekly.

L. Ron Hubbard wasn’t immediately receptive to the idea. He didn’t write about ray guns, machines, or robots, he told the executives (although many years later he did write a story about robots and mistaken identities—“Battling Bolto”—for another magazine). He wrote about people, he demurred. But Street & Smith’s leadership insisted: that was exactly why they were turning to him.

Still hesitant, L. Ron Hubbard agreed. As he recollected later, being a successful writer in other genres was hardly a reason to say no to the biggest publisher of the day.

John W. Campbell. Photo by Hubert Rogers.

At that point in the meeting, Mr. Hubbard recalls, the executives called in John W. Campbell, Jr., the twenty-eight-year-old writer-turned-fledgling-editor only recently hired to run Astounding Science Fiction. It would prove a historic, though not altogether pleasing, first encounter of powerful personalities.

As a writer, Campbell had given strong, early indications of his creative viewpoint with a five-part series called “The Mighty Machine.” Mr. Hubbard recalls that Campbell—the man “who dominated the whole field of sf as its virtual czar until his death in 1971”—had definite ideas about science fiction. These ideas at the time did not appear to include publishing the work of a writer whose reputation, however formidable, had been achieved with tales of adventure, the old West, and the strategies of detection.

Campbell argued and resisted, but the Street & Smith executives were firm. He was, they told him, “going to get people into his stories and get something going besides machines.” Campbell, at last, relented, and out of that somewhat contentious beginning, Ron Hubbard and John Campbell began a working relationship—and a friendship—with profound ramifications and enduring significance for the world of speculative fiction.

THE TRANSFORMATION OF SCIENCE FICTION

“The Dangerous Dimension,” L. Ron Hubbard’s first science fiction story (he later said he considered it a fantasy story, but critical opinion has consistently embraced it as innovative science fiction), was published in the July 1938 issue of Astounding Science Fiction. It would be the first of thirty-one short stories and novels that would appear in the magazine alone over the next twelve years and prove instrumental in making Astounding the undisputed epitome of popular science fiction.

“The Dangerous Dimension” as it appeared in the July 1938 issue of Astounding Science Fiction

With “The Dangerous Dimension,” sci-fi took a sharp, humanizing turn that would permanently transform it in ways that probably few who read the story at the time could envision. One reader, however—a young fan named Isaac Asimov—wrote a letter to Campbell asking, simply, for “some more from L. Ron Hubbard, please.”

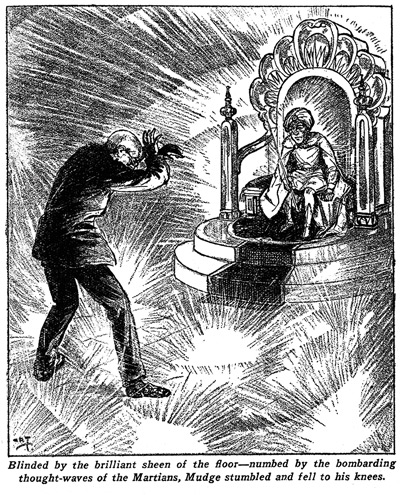

There are, of course, no ray guns, robots, or machine societies in “The Dangerous Dimension.” Instead, the “dimension” is the most dangerous of all: the mind of untidy, diffident Yamouth University philosopher Dr. Henry Mudge, who undergoes a startling personality change when he stumbles upon a mathematical door to a “negative dimension” that enables him instantly to go anywhere he thinks of—Paris, the Central Park Zoo, the Moon, Mars—even when he doesn’t want to go.

In just a few thousand words, L. Ron Hubbard had given science fiction an actual “person”—a fully realized, if initially unprepossessing, character “hero”—and entry into an imagined world extrapolated from the small, prosaic details of the real one. As always for L. Ron Hubbard, detail dominated: the paperwork clutter of Dr. Mudge’s office; his frayed carpet slippers and the glasses perched precariously on his nose; the single tuft of fur on an orangutan in the zoo; the saucers on a Parisian restaurant table. They are all tangible and immediate. Yet they are also the materials of the negative dimension L. Ron Hubbard describes, in a capsule parody of the long, tedious sermons on science that cluttered so much of earlier science fiction, as “no dimension. The existence of nothing as something—”

L. Ron Hubbard had, of course, fashioned an earlier story from a speculative, out-of-the-ordinary event in a commonplace setting—the impossible that could possibly happen to anyone—in his 1936 “The Death Flyer.” Revisiting the impossible as reality in “The Dangerous Dimension,” Mr. Hubbard promptly explored it even more extensively and with compelling effect. In his second story for Astounding, “The Tramp” (published in September through November 1938), he gave the concept an ominous twist. “The Tramp” tells of a hobo, suddenly endowed with phenomenal mental powers after experimental brain surgery saves his life, who attempts to seize control of the United States government.

“The Tramp,” which influenced many other L. Ron Hubbard stories to follow, meshes the speculative and the everyday by juxtaposing a hobo, a common enough feature of American life in those days, and the bizarre and dangerous telekinetic powers he acquires. L. Ron Hubbard would return again and again to this technique of blending the familiar and the arcane in greater and lesser ways—in the parallel worlds of Slaves of Sleep, the virtual realities of Typewriter in the Sky, the macabre shadows of Fear, and the farmer and his horse at an invisible intersection in time in “The Crossroads.”

Shortly after, L. Ron Hubbard began redefining science fiction, he was joined in the pages of Astounding Science Fiction by the first-published stories of such emerging contemporaries as A.E. van Vogt, Theodore Sturgeon, and the legendary Robert A. Heinlein.

THE BIRTH OF UNKNOWN

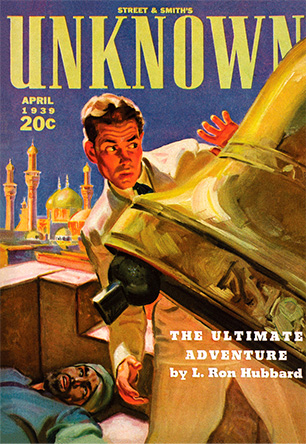

It soon became evident to John Campbell that many stories he was receiving, particularly from Ron Hubbard, belonged more clearly in the category of fantasy than sci-fi. He quickly convinced Street & Smith to launch a new magazine to accommodate the fantasy stories he was getting from L. Ron Hubbard. It was called Unknown and Campbell was its first editor. In its comparatively short lifespan—March 1939 to October 1943, when wartime paper shortages dictated its demise—Unknown became the foremost fantasy publication of its time.

“The Ultimate Adventure,” the first of fifteen stories by L. Ron Hubbard published in Unknown

L. Ron Hubbard’s innovative stories and novels contributed instrumentally to Unknown’s rapid rise and influence.

Even before Unknown’s debut, Campbell had learned of Ron Hubbard’s intimate familiarity with such fantasy works as Washington Irving’s Tales of the Alhambra and Sir Richard Burton’s translation of the tales of the Arabian Nights. Ron’s knowledge convinced Campbell that stories in that tradition to appear in the pages of Unknown would be exclusively L. Ron Hubbard’s.

As Campbell would lament, “I’m having a hell of a time getting the long stuff, because I consistently and firmly bounce anything below grade B+, and all the novels seem to run about grade C+.” And then he reminded his star writer, “Just because Unknown’s going, don’t forget Astounding still uses 85,000 words a month.”

As it turned out, that letter was a measure of how quickly—and how decisively—L. Ron Hubbard had moved to center stage in the world of speculative fiction.

Author and critic Damon Knight said it definitively when he wrote that L. Ron Hubbard “cut a swath across the science-fantasy world, the likes of which has never been seen again.”

—compiled from Master Storyteller:

An Illustrated Tour of the Fiction of L. Ron Hubbard

by William J. Widder