The vast mountains and limitless vistas of the frontier were not merely features of his imagination, although he endowed them with the richness of his creative spark. They were where he rode mustangs and range broncs at the age of three and a half, using a cut-down cavalry saddle, “the skirts of which had to be amputated so as to get the doghouse stirrups high enough for me to reach them.”

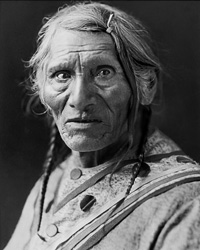

L. Ron Hubbard, Helena, Montana, 1914

In an excerpt from “A Chat with the Range Boss” in the June 1940 issue of Wild West Weekly, L. Ron Hubbard provided readers with some of the details of his youth:

“Two towns argue about my birth. Tilden Nebr., says I was born in Lincoln, Nebr.—and Lincoln says I was born in Tilden. I left those parts at the age of three weeks because grandpappy sold out in Nebraska (it was getting too tame) and got himself a spread in Oklahoma. Then it got too tame there and when I was two, I was hauled off to Kalispell, Montana. Because my folks disapproved of the way I walked they glued me to a McClellan saddle and there I stuck unto the age of seven.”

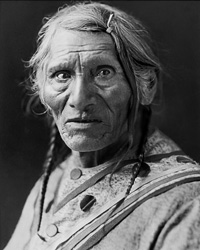

Old Tom, the bona fide Blackfoot medicine man who would eventually confer upon a young Ron Hubbard that rare status of blood brother.

As an author, he did not just invent colorful frontier characters—he recreated them, styled to be as authentic as the American frontier folk he remembered from his youth. “I grew up with old frontiersmen,” he recalled, “[with] cowboys, and had an Indian medicine man as one of my best friends.” A young Ron Hubbard was made a blood brother of the Blackfeet Indians, panned for gold, and traveled across open country that was harsh and imposing, even as the frontier was yielding to the 20th century and the encroachment of what was referred to as civilization.

But L. Ron Hubbard’s familiarity with the West went well beyond childhood adventures. He was also a dedicated student of the folklore and folkways of range riders and homesteaders, of Indian tribes and their turbulent pasts, of frontier towns and of the people who had crossed a continent to build them, and of the legends of the wild, wild west that lingered long after the original settlers were gone.

His fascination with the American frontier and his immersion in its history and culture was the foundation for his tales of the American West that appeared in virtually every pulp magazine of consequence for the better part of two decades.

To this immensely popular genre, Ron Hubbard brought his firsthand experience with fast rivers and sculptured canyons and his keen understanding of lawmen, desperadoes, prospectors, embattled rangers, and enterprising rustlers. He also shared his appreciation of the vast reaches of land and sky and the majesty of wild horses.

Most of all, L. Ron Hubbard captured the persona of a dawning nation in the shifting crosscurrents of history.

There was an irony to L. Ron Hubbard’s western fiction career. “My first western stories,” he later reflected, “were scornfully rejected since they were ‘not authentic,’ having been written by someone who had been west of Hoboken.” His sentiments were echoed elsewhere by one critic, for example, who deplored the general state of pulp westerns as “cowboy stories written by Manhattan bellhops.”

Whatever the initial resistance to L. Ron Hubbard’s western fiction, it proved to be brief and inconsequential. Within a year, spurred by their narrative power and authentic realism, his western stories began to appear under his own name and under such pen names as Barry Randolph and Ken Martin and later Winchester Remington Colt.

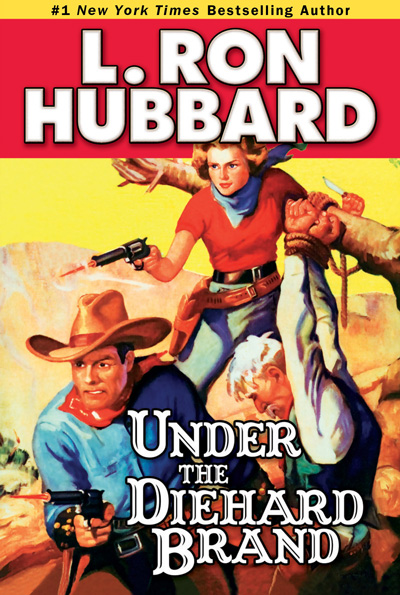

In 1938 alone, he had sixteen westerns published, many of them cover features, and all of them with his hard-hitting, trademark style. Among some of the noteworthy were “Six-Gun Caballero” and “The Toughest Ranger,” both of which appeared in Street & Smith’s Western Story. That same year saw the publication of the whimsically engaging “When Gilhooly Was in Flower,” which he wrote under the name of Barry Randolph for Romantic Range and the gritty “Under the Diehard Brand” in Western Aces. One memorable 1938 issue of Five Novels Monthly featured both Barry Randolph’s “Branded Outlaw” and L. Ron Hubbard’s “The Lieutenant Takes the Sky,” an unusual literary double-header.

In 1938 alone, he had sixteen westerns published, many of them cover features, and all of them with his hard-hitting, trademark style. Among some of the noteworthy were “Six-Gun Caballero” and “The Toughest Ranger,” both of which appeared in Street & Smith’s Western Story. That same year saw the publication of the whimsically engaging “When Gilhooly Was in Flower,” which he wrote under the name of Barry Randolph for Romantic Range and the gritty “Under the Diehard Brand” in Western Aces. One memorable 1938 issue of Five Novels Monthly featured both Barry Randolph’s “Branded Outlaw” and L. Ron Hubbard’s “The Lieutenant Takes the Sky,” an unusual literary double-header.

L. Ron Hubbard wrote other notable westerns, of course—“The No-Gun Gunhawk” (1936), whose horseman sent dust “rolling up in a great yellow fog toward the blue”; the unforgettable “Stranger in Town” (1949); “Hoss Tamer” (1950) which later aired on NBC’s celebrated Tales of Wells Fargo television series; and “Shadows from Boot Hill” (1940), his only western fantasy.

“Hope your readers like ‘Shadows from Boot Hill.’ Truth is that the old West was superstitious in the extreme and Injun lore reeks with more fantasy than the Arabian Nights.

“Tell the readers to yelp loud and long if they like my Western fantasy—and to keep kinda quiet ifn they don’t.

“The Old Word Wrangler,

“L. Ron Hubbard.”

—compiled from Master Storyteller:

An Illustrated Tour of the Fiction of L. Ron Hubbard

by William J. Widder

In 1938 alone, he had sixteen westerns published, many of them cover features, and all of them with his hard-hitting, trademark style. Among some of the noteworthy were

In 1938 alone, he had sixteen westerns published, many of them cover features, and all of them with his hard-hitting, trademark style. Among some of the noteworthy were