Hard-Boiled Detective Thrills, Chills & Murder Mysteries

The butler did it…

Or did he?

The most final and irreversible crime is murder. Murder is sometimes personal, often bloody, usually messy and almost always cause for investigation by some hard-boiled detective.

Having traveled the world and witnessed man from the desperate gutters of Peking to the swanky society clubs of New York, L. Ron Hubbard used the world as his research lab from which to spin tales of spellbinding suspense and coldhearted murder. Murder mysteries that were original, unique and unforgettable because Ron knew the beat and understood how to conduct an authentic investigation.

The Usual Suspects

Is there a method to the madness?

Maybe…

While murder is mad, unraveling the method cannot be.

L. Ron Hubbard, like many renowned authors of the past century, understood the need to rub shoulders with real people who lived the types of lives that populated his stories.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Take note. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle would have never been able to conjure up the master of deduction himself, Sherlock Holmes, had it not been for his academic work as a student at the University of Edinburgh—first with Dr. Joseph Bell, who specialized in criminal psychology (after whom Holmes was modeled), and later with Professor Andrew Maclaglan, a forensic medicine expert, who taught Doyle how to observe the details and clues that led to the precise causes of death.

Dashiell Hammett

The same is true of Dashiell Hammett, creator of fictional famous detectives such as Sam Spade (immortalized on the screen by Humphrey Bogart) and Nick and Nora Charles. Hammett grew up on the mean streets of Philadelphia and worked as a private detective with the Baltimore and San Francisco branches of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency—and had the cuts and scars from scraps with criminals to prove it.

When it came to L. Ron Hubbard’s mystery and detective fiction—he made no exceptions and pulled no punches. To conjure a memorable tale, he knew the fiction had to be based on fact.

Digging Up the Evidence

L. Ron Hubbard started his pulp fiction writing career in Encinitas, California (in part to recover from bouts of malaria contracted while on an expedition in Puerto Rico), but he jumped coasts and settled in the heart of the New York publishing empire in late 1934. His success as a headlining author for the pulps was due to having a working knowledge of what he was writing about, and that included the science of investigating a crime.

Francisca Rojas was found guilty by comparing her fingerprint to that left on a door

More than the subject of hit CSI television dramas, forensic science has evolved and improved over the years. (Forensic analysis has been documented at least as far back as the “Eureka” legend of Archimedes, 287-212 BC—even though, surprisingly, police only started using fingerprints for evidence in 1892 when Juan Vucetich solved a murder mystery case in Argentina by examining a bloody fingerprint on a door.)

So it was that Ron’s tenacious demand for authenticity and interest in forensics served him well when, at the age of 25, he was named president of the New York Chapter of the American Fiction Guild.

Among his duties was the unearthing of speakers for the Friday night gatherings in the lounge of the Hotel Knickerbocker. His earnest interest in presenting facts in fiction can be seen in this telling passage from a letter inviting the highly regarded New York City Police Commissioner, Lewis J. Valentine, to attend one of these meetings:

“Very few of our detective writers—and by that I mean some of the biggest names in such fiction—have ever seen the inside of a station house. Most of this material is turned out blind. The writers do not seem to realize that they hold a mighty bludgeon of influence with their stories.…

“We want, frankly, a closer alliance between fiction and fact. We have accomplished that in other fields. The Department of Justice has given writers immeasurable aid so that G-man fiction is gradually becoming accurate and there is, therefore, a better public understanding of that work.”

The Art of Detection

When writing about the Old West, Ron was able to draw from his frontier experiences in Montana. For sea adventures, he could draw on his sailing expeditions on the Alaska coastline, or his five-thousand-mile 1932 Caribbean Motion Picture Expedition—and his barnstorming adventures across America in the golden age of flight helped power his whirlwind air tales.

But when it came to creating a convincing cadre of hard-boiled detectives and alleyway thugs, New York was the place to be. Case in point: the Paul Ernst murder mystery parties he attended where guests were required to solve a mock murder, and talk of dastardly deeds finally grew so heated that neighbors telephoned the police.

For his detective fiction, he interviewed law enforcement officials, police officers, and federal investigators. He even developed a long-term friendship with New York’s chief medical examiner, who, Ron subsequently recalled, introduced him to the fascinating realities of forensic medicine. “The morgue,” the coroner assured him, “is open to you anytime, Hubbard.”

He even invited the coroner to share his professional expertise with New York City Guild members over lunch. “They would,” Ron recounted afterward, “go away from the luncheon the weirdest shades of green.”

Aerial view of Sing Sing Prison

In addition to his research with experts in the field of detection, he continued to enlarge his range of study, including paying a visit to the New York State Correctional Facility at Ossining—the notorious Sing Sing.

And so it was that he was able to craft two-fisted tales of crime-fighting suspense that were published in Phantom Detective, Popular Detective, Mystery Novels and Detective Fiction and other popular fiction magazines.

Expect the Unexpected

L. Ron Hubbard’s meticulous research and real-life adventures were the ingredients he used to create some of his most memorable crime stories.  “Dead Men Kill,” which appeared in Thrilling Detective in 1934, followed a hard-boiled detective and a coroner trying to solve a series of crimes apparently committed by men who had already died. Hubbard enriched “Dead Men Kill” with a glimpse of the voodoo culture he had encountered during his West Indies odyssey two years earlier, adding an uncommon flavor to a genre that was one of the pulps’ staple formulas.

“Dead Men Kill,” which appeared in Thrilling Detective in 1934, followed a hard-boiled detective and a coroner trying to solve a series of crimes apparently committed by men who had already died. Hubbard enriched “Dead Men Kill” with a glimpse of the voodoo culture he had encountered during his West Indies odyssey two years earlier, adding an uncommon flavor to a genre that was one of the pulps’ staple formulas.

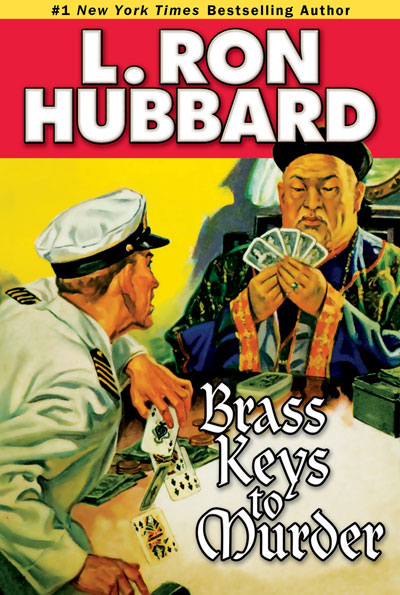

Another notable Hubbard detective yarn,  “Brass Keys to Murder,” appeared in the April 1935 Five-Novels Monthly under the pen name of Michael Keith, about a naval lieutenant who has less than 48 hours to clear his name of the murder of his own father, a ship captain in the merchant marine. “Brass Keys” thus made Hubbard a double-barreled threat in Five-Novels, where he had already established himself as a front cover standard-bearer for his adventure stories.

“Brass Keys to Murder,” appeared in the April 1935 Five-Novels Monthly under the pen name of Michael Keith, about a naval lieutenant who has less than 48 hours to clear his name of the murder of his own father, a ship captain in the merchant marine. “Brass Keys” thus made Hubbard a double-barreled threat in Five-Novels, where he had already established himself as a front cover standard-bearer for his adventure stories.

He also let his imagination run wild in his detective fiction. For example, in “The Mad Dog Murder” (Detective Fiction Weekly, June 1936), mystery and whimsy came together in a story about a Pekingese suspected of foul play. Hubbard later recalled:

“Every once in a while some friend of mine would tear in and have to have a detective story or something of the sort, and I’d write one. But I always balked at writing detective stories as detective stories, so I used to take all the taboos in detective story parlance and patterns and write the exact reverse of the taboo, knowing then that I had a wide-open field—knew then that it was original.

“And one publisher of a very famous detective magazine (that used to sell some horrendous numbers of copies) unfortunately issued a whole list of taboos—stories he would not accept under any condition. He wouldn’t accept a story without tremendous action in it. He wouldn’t accept a story without a good villain, so on. Well, that was a setup.

“To the first one, it was very simple to answer that request. I just wrote a story about the sergeant and the detective with spring fever, and they sat with their feet on the desk and waited for a watch to run down. And at the end of the story, because the watch had run down at a certain hour, they went and arrested the murderer. But you didn’t even attend their arrest. A story must have action. And it’s just no action, no motion. He bought it. He couldn’t help it, it just went right straight through.

“The second story—a story must have a good villain, a rough villain, a tough villain—the murderer was a Pekingese. This was my peculiar method of making nothing out of detective story writers that I think are rather humorous.”

Original illustration from L. Ron Hubbard’s “Mad Dog Murder”

Case Closed

L. Ron Hubbard’s murder mysteries, as do his other works, draw on the vast mystery of the human condition and a broad knowledge of the world and its cultures. With these, he wove stories capable of creating alternate realities for readers all over the world. It is that capability that makes his work so enjoyable and accessible to all. Even so, his mysteries make up just a portion of his grand literary legacy that to date has resulted in more than 350 million of his works in distribution and four Guinness World Records, including “most published” and “most translated author” of all time. For more information, go to LRonHubbard.org.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!