L. Ron Hubbard’s Romance with the Old West

Born to the Saddle

L. Ron Hubbard loved the Old West and respected its ways. Both his anecdotes of growing up in the wide, open spaces of Montana, an immense country that “swallows men up rather easily,” and the tales he spun for the western story magazines during the golden era of pulp fiction leave a lasting impression of his admiration for the land and people that helped shape his youth.

Despite his status as one of the most renowned and prolific of twentieth-century writers, many readers are pleasantly surprised to discover that Ron was also one of the most popular authors of western stories when westerns dominated America’s fiction markets in the 1930s and 1940s.

Ron’s affinity for the West was so strong that the image of a cavalry officer charging into battle astride a galloping horse was the logo that appeared on his personal letterhead during the days when he earned his reputation as one of the premier writers of popular fiction.

Ron’s affinity for the West was so strong that the image of a cavalry officer charging into battle astride a galloping horse was the logo that appeared on his personal letterhead during the days when he earned his reputation as one of the premier writers of popular fiction.

Horses and horsemanship are integral elements of any story about the Old West. Not only was the horse the most common means of transportation of the day, it was also the partner-in-survival of virtually everyone in a big and often harsh land. And even though horsemanship is rarely mentioned in the extensive list of skills mastered by L. Ron Hubbard, it is certainly one in which he was expert. Having grown up in the rugged Northwest, when the spirit of the frontier still pulsed in daily life, Ron was no stranger to saddle, reins and stirrup—and even an occasional bucking bronco:

I was riding broncs at three and a half and was a “bounty hunter” for gophers at the age of five and even in ’39 broke a rodeo-trained bucking horse no one else could ever ride.

His grandfather, a Montana rancher, raised blooded stock and owned several famous studs. Ron lived with his grandparents for several years, and even as a young child was expected to pull his weight from the moment he was up on his first mount:

His grandfather, a Montana rancher, raised blooded stock and owned several famous studs. Ron lived with his grandparents for several years, and even as a young child was expected to pull his weight from the moment he was up on his first mount:

It did not matter how often I was thrown; when a mustang exploded under me, goaded on by a frozen saddle blanket, it was I who was always scolded and cautioned not to be mean to horses. It never seemed to surprise these adults that I remained alive under all this, and it did not seem to them unusual to ask somebody to ride a wild range bronc with a single snafflebit, no quirt, no spurs and a cut-down McClellan cavalry saddle, the skirts of which had to be amputated so as to get the doghouse stirrups high enough for me to reach them.

One amusing story Ron told friends was an adventure he had as a boy while riding his horse into Helena, the capital city of Montana:

I had an argument with the SPCA (Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals) when I was six. I had managed to bring to curb, by running him into a brick wall, a 1,200-pound Kentucky saddler. Somebody had placed it off as a riding horse, and I couldn’t stop him. He was going places, and he wasn’t bright enough to climb the wall or anything imaginative like that, so he merely ran into it. And, of course, he fell down. So I sat down on him and waited for him to more or less come to and shake himself out of it.

This lady came up, and lo and behold, it was the SPCA, because this happened within a half of a block of the capital of Helena, Montana. And they had quarters right in that vicinity in those days. She started to sound off about cruelty to horses.

I don’t know where she got off bawling out a six-year-old boy who had just almost lost to a 1,200-pound horse, but we had quite an argument— which almost put me in police court—which was to the effect I said rather profanely that she ought to engage herself in forming a society for prevention of cruelty to children by horses. And that she belonged to the wrong gang.

But Ron’s western experience was by no means limited to horses. He studied the folklore and folkways of a diverse assortment of range riders, homesteaders and other western citizenry inhabiting the makeshift towns they built essentially overnight on little more than hopes and dreams:

I grew up with old frontiersmen, cowboys and had an Indian medicine man as one of my best friends.

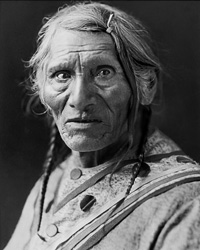

Old Tom, the bona fide Blackfoot medicine man who would eventually confer upon a young Ron Hubbard that very rare status of blood brother.

Thus, when L. Ron Hubbard chose to write western fiction, his best research sources were, in fact, his own recollections of characters and setting captured in his youth.

“My first western stories,” L. Ron Hubbard once said, “were scornfully rejected since they were ‘not authentic,’ having been written by someone who had been west of Hoboken.”

His remark was only partially tongue in cheek, for although westerns were by far the most enduring and popular stories in the pulp magazines during the first half of the twentieth century, most were written by easterners who were more familiar with the streets of New York City than the plains of Nebraska or the cattle trails of Texas. Ron wasn’t limited by unfamiliarity. He lived in the West as the frontier yielded to the internal combustion engine and horses deferred to automobiles. Not only had he been made a blood brother of the Blackfeet Indians, but he had panned for gold and traveled across country that was still harsh and dangerous.

By the summer of 1933, Ron had moved from the East Coast of the United States to San Diego, California, and then from there he launched his entry into the highest echelons of the pulp fiction markets. He set a goal to write a story a day and send each one out to the pulp magazines until they sold.

Ron’s persistence soon paid off. Before the end of the year, his first stories began to sell—to Thrilling Adventures, to Phantom Detective, to Five Novels Monthly, to Thrilling Detective, and to the Street & Smith publication Cowboy Stories.

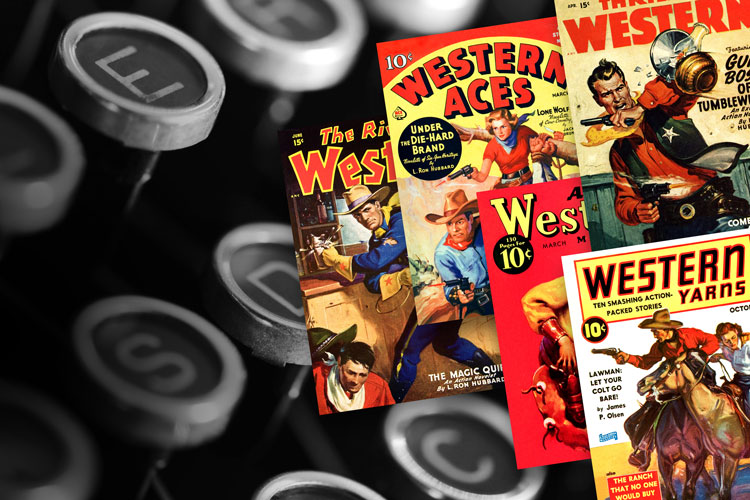

Although most prolific in those days as an adventure writer, and then later achieving legendary status in the fields of science fiction and fantasy, Ron ultimately published over three dozen cowboy tales for virtually every magazine in the field—under his own name, and under the pennames Ken Martin, Winchester Remington Colt and Barry Randolph.

Ron’s stories filled the pages of a long list of these publications, including Western Stories, Cowboy Stories, All Western, Western Yarns, Western Aces, Western Action Magazine, Famous Westerns and even Romantic Range.

The surviving pulp magazines that featured Ron’s tales of adventure, courage, action and humor, set against the western panorama of vast ranges of open land, towering mountain peaks, roaring rivers and boom, bust and ghost towns and peopled by all the colorful characters associated with the Old West, are today part of valuable collections owned by collectors of western lore, art and literature.

Ron’s western stories are truly a legacy of realism and entertainment. They are windows into the imagination of a great writer who really knew his subject.

Experience the Wild West for yourself in L. Ron Hubbard’s Western Collection, available in print and as multicast audiobook productions.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

This is interesting information! Thanks.