The Real True Detectives

Gritty, raw, detectives stories, like those portrayed in the HBO series, True Detective didn’t happen overnight. The evolution of the detective genre—books and stories that tantalize us with murder mysteries and crime drama—is a phenomena that taps into our love of solving a good mystery.

True Detective also delves into our crushes on the personalities that drive a gumshoe story. The investigators and police detectives, like those portrayed by Vince Vaughn and Colin Farrell in the latest installment, and Woody Harrelson and Matthew McConaughey in the first season, are insanely fun to watch.

One of the players who made true detective stories so popular was L. Ron Hubbard. We’ll take a look at how Hubbard developed some of the enduring detective stories that still resonate with us today, but first let’s look at the history that led to hit shows like True Detective.

The Birth of the Detective Story

While Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s character, Sherlock Holmes is one of the most famous, he wasn’t the first literary detective. That honor generally goes to C. Auguste Dupin, the character created by American author Edgar Allan Poe whose mysteries and literary works were popular in both the US and Europe and, as a result, his stories influenced writers on both sides of the pond.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of Sherlock Holmes said, “Each [of Poe’s detective stories] is a root from which a whole literature has developed…. Where was the detective story until Poe breathed the breath of life into it?”

Edgar Allan Poe’s character C. Auguste Dupin first appears in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” in 1841, wherein he is described as having a logical method of problem solving with an emphasis on intense reading for clues—characteristics that would have a lasting influence on detective fiction. Dupin was not, however, a private detective. In fact, Poe’s character was created before the word “detective” had even been coined. The murder mystery solving Dupin enjoyed a short literary career spanning only three novels—but the effect would be lasting.

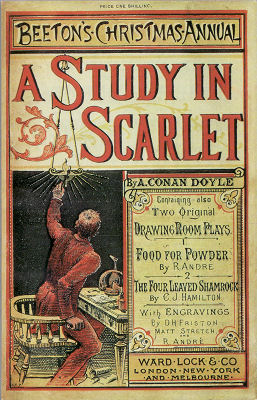

Almost five decades later, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes would make his debut in “A Study in Scarlet” (1887) and the private sleuth would go on to enjoy a very long life in sixty stories. In the preface to the book The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Conan Doyle acknowledged the influence of Poe: “Edgar Allan Poe, who, in his carelessly prodigal fashion, threw out the seeds from which so many of our present forms of literature have sprung, was the father of the detective tale, and covered its limits so completely that I fail to see how his followers can find any fresh ground which they can confidently call their own.”

Almost five decades later, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes would make his debut in “A Study in Scarlet” (1887) and the private sleuth would go on to enjoy a very long life in sixty stories. In the preface to the book The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Conan Doyle acknowledged the influence of Poe: “Edgar Allan Poe, who, in his carelessly prodigal fashion, threw out the seeds from which so many of our present forms of literature have sprung, was the father of the detective tale, and covered its limits so completely that I fail to see how his followers can find any fresh ground which they can confidently call their own.”

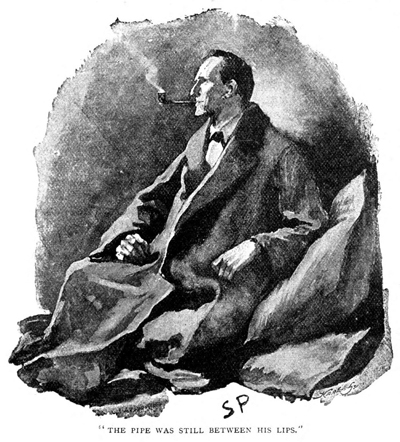

The model Conan Doyle used for Holmes, however, was another person completely: “Sherlock Holmes is the literary embodiment . . . of my memory of a professor of medicine at Edinburgh University [Dr. Joseph Bell], who would sit in the patients’ waiting-room . . . and diagnose the people as they came in, before they had even opened their mouths. He would tell them their symptoms, he would give them details of their lives, and he would hardly ever make a mistake.”

The model Conan Doyle used for Holmes, however, was another person completely: “Sherlock Holmes is the literary embodiment . . . of my memory of a professor of medicine at Edinburgh University [Dr. Joseph Bell], who would sit in the patients’ waiting-room . . . and diagnose the people as they came in, before they had even opened their mouths. He would tell them their symptoms, he would give them details of their lives, and he would hardly ever make a mistake.”

The modern versions of Sherlock Holmes, like the hit films starring Robert Downey Jr. and Jude Law, not to mention the Benedict Cumberbatch TV show Sherlock, are a testament to how this beloved character has stood the test of time. Ironically, Sherlock’s creator grew tired of his own character and Doyle kills him off in “The Final Problem.”

Fan reaction to Holmes’ demise was immediate and adverse and pressure from both the fans and publisher finally persuaded Doyle to bring Holmes back, which he does in The Hound of the Baskervilles—a story that takes place before “The Final Problem” and is narrated by his stalwart assistant, Dr. Watson. Later, in “The Adventure of the Empty House” Holmes is back for good and explains to a stunned Watson that he had faked his death to fool his enemies.

The Golden Age of Detective Fiction

The period of the 1920s to 1930s is generally referred to as the Golden Age of Detective Fiction. Among the famous British detective authors of the time is “Queen of Crime” Agatha Christie who did not create a singular sleuth, but had various characters, both amateur and professional. Among the most notable were Miss Marple, an elderly spinster and amateur consulting detective and, of course, detective Hercule Poirot. Although Poirot was not based on any particular person, Christie thought that a Belgian refugee, a former great Belgian policeman, would make an excellent detective for her book The Mysterious Affair at Styles, and thus the start of what was to be a very long literary career for her new character. Detective Poirot would go on to appear in no less than 33 novels, one play and 50 short stories before his literary “death” in the novel Curtain. In testament to his popularity, Poirot was the only fictional character to receive an obituary on the front page of The New York Times.

The Birth of the American Hard-Boiled Detective

By the 1920s a distinctively American detective fiction—the hard-boiled detective—emerged from popular pulp magazines Black Mask, Dime Detective, Detective Fiction Weekly and Thrilling Detective. Influenced by an increase in violence from organized crime caused by Prohibition and then the Great Depression, the hard-boiled detective was tough and unsentimental, with a gritty realism, where the crime often took place in the underbelly of the city in contrast to the country house populated by cooks, butlers and back-stabbing relatives of the staid British “whodunits.”

Some of the popular authors whose names graced the pulps include H.P. Lovecraft, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Louis L’Amour, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Erle Stanley Gardner, Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein and L. Ron Hubbard.

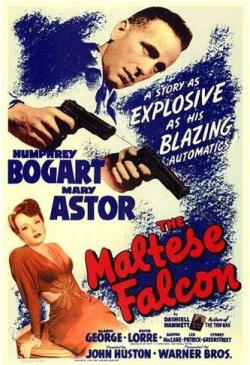

Crime fiction author Carroll John Daly is credited with creating the first hard-boiled story, “The False Burton Combs” published in Black Mask magazine in 1922 and the first hard-boiled detective, Race Williams, a rough-and ready character with a sharp tongue. However, it was Sam Spade, the private detective and protagonist of Dashiell Hammett’s 1930 novel The Maltese Falcon, who is generally recognized as the model for the hard-boiled detective, forever memorialized by Humphrey Bogart’s portrayal in the film version.

Crime fiction author Carroll John Daly is credited with creating the first hard-boiled story, “The False Burton Combs” published in Black Mask magazine in 1922 and the first hard-boiled detective, Race Williams, a rough-and ready character with a sharp tongue. However, it was Sam Spade, the private detective and protagonist of Dashiell Hammett’s 1930 novel The Maltese Falcon, who is generally recognized as the model for the hard-boiled detective, forever memorialized by Humphrey Bogart’s portrayal in the film version.

As Hammett describes his character: “Spade has no original. He is a dream man in the sense that he is what most of the private detectives I worked with would like to have been and in their cockier moments thought they approached. For your private detective does not—or did not ten years ago when he was my colleague—want to be an erudite solver of riddles in the Sherlock Holmes manner; he wants to be a hard and shifty fellow, able to take care of himself in any situation, able to get the best of anybody he comes in contact with, whether criminal, innocent by-stander or client.”

L. Ron Hubbard and the Golden Age of Pulp Fiction

As one of the prolific and popular writers during the Golden Age of Pulp Fiction, L. Ron Hubbard started his writing career writing adventure and detective stories.

Hubbard had a variety of protagonists in his mysteries, including ace operative and undercover narcotics agent Bob Clark, a hard-boiled detective who would be featured in two of his mystery stories, The Carnival of Death and Murder Afloat. These stories are not intricately layered, puzzles-within-a-puzzle stories, but rather gritty, sharp-edged crime stories with the hero pursuing ambiguous clues and uncertain truth despite the danger it puts him in so that justice can be served.

Hubbard had a variety of protagonists in his mysteries, including ace operative and undercover narcotics agent Bob Clark, a hard-boiled detective who would be featured in two of his mystery stories, The Carnival of Death and Murder Afloat. These stories are not intricately layered, puzzles-within-a-puzzle stories, but rather gritty, sharp-edged crime stories with the hero pursuing ambiguous clues and uncertain truth despite the danger it puts him in so that justice can be served.

To create an authentic foundation for his detective fiction, Hubbard interviewed a wide spectrum of law enforcement official, police officers and federal investigators. After moving to New York in 1934, he struck up a long-term relationship with the city’s chief medical examiner who introduced the young writer to the fascinating realities of forensic medicine. Later, as the youngest-ever president of the New York Chapter of the American Fiction Guild, Hubbard lends his leadership skills to a group that includes Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammet and Edgar Rice Burroughs. As president he invited the coroner to share his professional expertise with Guild members over lunch. “They would,” Hubbard recalled, “go away from the luncheon the weirdest shades of green.”

Hubbard, meanwhile, would continue to enlarge his range of study, paying a visit to the state correctional facility at Ossining, New York—the notorious Sing Sing—and, in the late 1940s, becoming a special officer in the Los Angeles Police Department.

As he put it, “I believe that the only way I can keep improving my work and my markets is by broadening my sphere of acquaintanceship with the world and its people and professions.” It was his extensive research and attention to detail that gave his mysteries and detective stories an unmistakable seal of realism.

Other articles and resources you may be interested in

Hard-Boiled Detective Thrills, Chills & Murder Mysteries

L. Ron Hubbard Master of Thrilling Detective

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!