Typewriter in the Sky

Review by Mike Resnick

There’s a type of science fiction that’s less than a century old.

It began with a splash, was too challenging for most practitioners, appeared sporadically (but always causing major waves within the field), and finally began appearing with some regularity by its fiftieth birthday.

It is known as recursive science fiction, which means, quite literally, science fiction about science fiction—and the handful of good ones stick around forever. There’s Fredric Brown’s What Mad Universe, which takes place in a universe that a science fiction editor thinks one of his adolescent readers dreams about. There’s Robert A. Heinlein’s The Number of the Beast, in which characters from Heinlein’s previous books show up on worlds and in societies that were created—and sold—by other science fiction writers. There were Galaxies and Herovit’s World and Gather in the Hall of the Planets and half a dozen short stories and novelettes by Barry N. Malzberg, who spent a goodly portion of his career exploring the possibilities of recursive science fiction.

And it’s far from done. As editor of Galaxy’s Edge, a science fiction magazine, I recently bought a story by former Worldcon Guest of Honor Gregory Benford titled “Rave On,” about a meeting (which in real life never took place) between science fiction superstars Harlan Ellison and Philip K. Dick.

So much for recursive science fiction’s ongoing history. But it had to start somewhere. With Luigi Pirandello’s brilliant Six Characters in Search of an Author and other examples, sooner or later some science fiction writer had to examine the concept and say (or think), “Hey, I’ll bet that would work in our field!”

We’re just damned lucky it was a man with the skills, sense of humor, and commercial instincts to do it right, or recursive science fiction might have died one book into its life. The man was L. Ron Hubbard, who was writing at the top of his form, and three-quarters of a century later some of our finest practitioners are still following his lead.

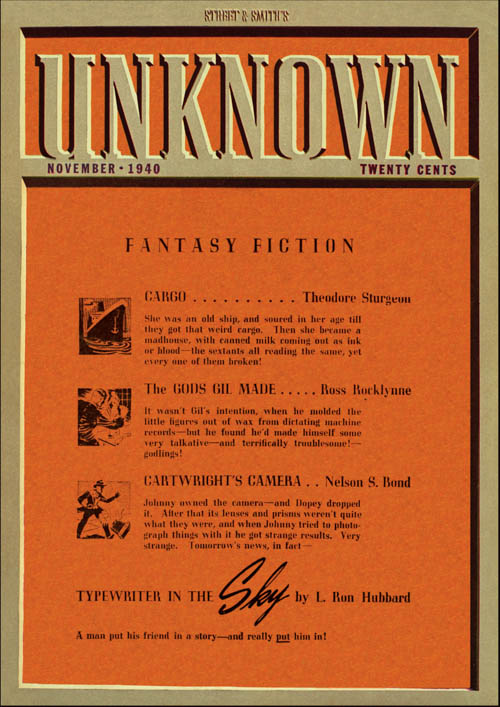

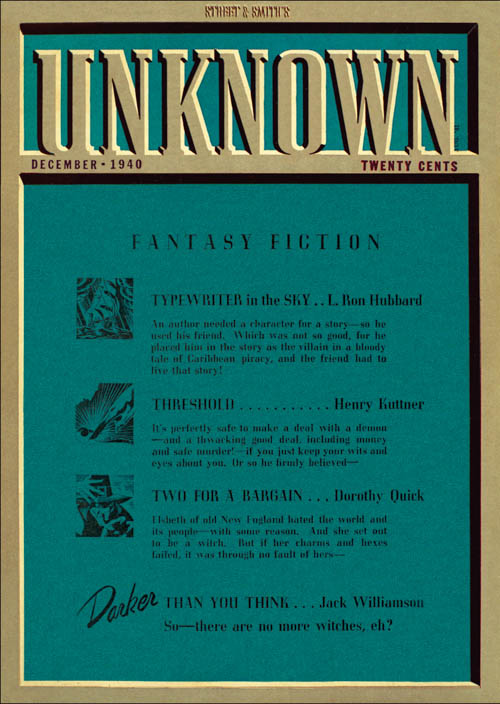

Typewriter in the Sky was originally serialized in Unknown magazine.

You haven’t heard of it? Well, it only lasted four years. It began in 1939, and the wartime paper shortage killed it—and dozens of other magazines—in 1943.

But if you’re a fan of the field, you’ve probably heard of it anyway, and you’ve surely read stories from it, for it was—and remains—by consensus the greatest fantasy magazine of all time. It featured such major figures—who were not so major back then—as Robert A. Heinlein, Henry Kuttner, Jack Williamson, A. E. van Vogt, Theodore Sturgeon, Fritz Leiber, L. Sprague de Camp, Fredric Brown, and Eric Frank Russell. Isaac Asimov tried five times to sell to it and came away empty-handed.

And the major contributor to Unknown during its brief lifetime was Hubbard, who sold them eight novels. Among them was the classic Fear, but the one that by today (2019) clearly had the most influence on the field was Typewriter in the Sky.

Nor am I alone in praising it. For example:

Frederik Pohl: “Fans and other writers were doing variations on that for years.”

James Gunn: “With the publication of Unknown, Hubbard became even more of a significant figure, with stories like Fear and Typewriter in the Sky.”

Damon Knight: “The story ends with three immortal lines: ‘Up there— God? In a dirty bathrobe?’ ”

George Alec Effinger: “Typewriter in the Sky is one of the most influential books in the history of fiction. I’ve written some recursive fiction myself, and I think of Hubbard every time I sit down at my keyboard in my tattered bathrobe.”

Algis J. Budrys: “I have read it many times since its first appearance, and it never flags, it never gets old.”

And, to quote the ultimate authority, the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: “Typewriter in the Sky, a slyly effective self-referential fabulation, may be Hubbard’s most permanently memorable work.” Do you know how many hundreds of fiction books and stories that encompasses?

So what you have here is an acknowledged classic, a forerunner of an entire subgenre, churned out for a pulp magazine—and unlike so many classics, so many forerunners, and so many pulp stories, it’s still fun to read eight decades later.

One thing about Hubbard is that he was always readable, and his style never grows old or outdated. Typewriter in the Sky pleased pulp readers in 1940. It pleased science fiction aficionados in its 1951 Gnome Press hardcover edition (Gnome was one of the truly great science fiction specialty publishers). It pleased the general readership in its 1977 Popular Library paperback edition. It pleased a fair-sized cross-section of the public in its 1995 hardcover edition. And I can say without hesitation that this edition is going to keep Typewriter’s record of pleasing readers intact.

Nor am I a latecomer to this conclusion. For several decades, I’ve been praising Typewriter in the Sky for its skill and innovation in various articles.

And nothing’s changed.

Well, one thing has. A new generation of readers gets to read the delightful novel that basically created the recursive science fiction genre, and was surely the first to show what that genre could do. This may not seem like much today, where writers meet themselves in their own stories, or transport themselves into friends’ universes, but trust me, it was a lot harder when there were no examples, nothing to guide Hubbard as he basically created the subgenre.

And while that’s certainly important, and worthy of critical attention from scholars and academics, the main thing about Typewriter in the Sky—it was true in 1940 and it’s true today—is that it’s fun to read.

So let’s end this introduction and let you climb onto the roller coaster that Hubbard created eighty years ago for your enjoyment. It goes as fast as ever, the laughs haven’t diminished over the years, and it’s just too much fun to hold in academic awe as you’re reading it.

I envy you already.

—Mike Resnick

Mike Resnick was a popular and prolific American science fiction author. According to Locus, he was the all-time leading award winner, for short science fiction. He was the winner of five Hugos, a Nebula and other major awards in the United States, France, Spain, Japan, Croatia and Poland and has been short-listed for major awards in England, Italy and Australia. He authored 76 novels, over 280 stories, 3 screenplays and was the editor of 41 anthologies.

“Typewriter in the Sky” Part 1

by L. Ron Hubbard

Publication date: November 1940

Original publication: Unknown

by L. Ron Hubbard

Publication date: December 1940

Original publication: Unknown

by L. Ron Hubbard

Publication date: June 2019